Ograndskad översättning ~ 2022-03-15

Bahá'u'lláhs tillbakadragande till Kurdistan

Baha'u'llah's Seclusion in Kurdistan

by

Bijan Ma'sumian

Publiserad i Deepen, 1:1, sidor 18-26

Hösten 1993

Se Källan elller Här

*

Innehåll

• Bahá'u'lláhs tillbakadragande till Kurdistan »

• Bahá'u'lláhs landsförvisning till Irak »

• Azals ledarskap »

• Skriften om all tings föda »

• Azals reaktion »

• Tillbakadragandet till Kurdistan »

• Sulaymáníyyih »

• Livet bland sufierna »

• Bahá'u'lláhs återkomst till Baghdád »

* * *

Bahá'u'lláh och Naqshbandí Sufierna

i Iraq, 1854-1856 »

av

Juan Ricardo Cole

publiserad i Studies in the Bábí and Bahá'í Religions,

Volume 2, sidor 1-28

Los Angeles: Kalimat Press

1984

Se Källan

Baha'u'llah's Seclusion in Kurdistan – en

Historians have always experienced difficulty in reconstructing the precise nature of the events that led to Bahá'u'lláh's two-year retirement to Iraqi Kurdistan (1854-1856). Accounts of His daily life in that region also remain, for the most part, sketchy.

Much of this ambiguity may be due to two distinct factors. First, until recently few scholarly attempts were made to provide a clear and concise picture of the events surrounding Bahá'u'lláh's decision to withdraw from the Bábí community of Baghdád. Second, most of what is known today about Bahá'u'lláh's stay in Kurdistan relies either on His own personal accounts or on inferences made from His works penned during that period. None of Bahá'u'lláh's followers shared His self-imposed exile and, consequently, no comprehensive history of those days is left to posterity. However, recent publication of several scholarly works have paved the way toward shedding more light on this rather obscure period in Bahá’í history. The purpose of this paper is to draw upon these new sources and present a logical framework for a better understanding of this significant phase in the metamorphosis of the Bábí religion into the Bahá’í Faith.

Bahá'u'lláh's Exile to Iraq - en

Following the failed attempt on the life of Násirí'd-Din Sháh, the King of Persia, by a small band of radical Bábís, the entire Bábí community went under suspicion. The would-be assassins were immediately arrested and the more well-known figures were fervently sought.

At the time of the assassination attempt, Bahá'u'lláh, who had recently returned from pilgrimage to the holy cities of Najaf and Karbilá, was in Afcha, a summer resort near Tehrán. Although He condemned the actions of these radicals, He realized that He might be sought by the government officials as a Bábí leader and He chose to surrender Himself to the authorities. He was taken to a prison where He remained for four months (the Siyyah Chál, or ”Black Pit”). During that time, according to His later testimony, He had several mystical experiences which convinced Him that He was the One whose appearance the Báb had foreseen and who was destined to become the next leader of the Bábí movement.

Táherzádeh, Adib, Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh, Vol. I. Oxford: George Ronald, Publisher, 1974 p. 10.

In the meantime, at the insistence of Mírzá Májíd-í-Ahi, the Secretary to the Russian Legation in Tehrán and brother-in-law of Bahá'u'lláh, Prince Dolgorki, the Russian Ambassador, pressured the government of Násirí'd-Din Sháh to either produce evidence against Bahá'u'lláh or to release Him. In absence of any proof, Bahá'u'lláh, Who was initially condemned to life in prison, was forced by the King to choose a place of exile for Himself and His family.

Balyuzi, M. H., Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory. Oxford: George Ronald, Publisher, 1980, p. 99.

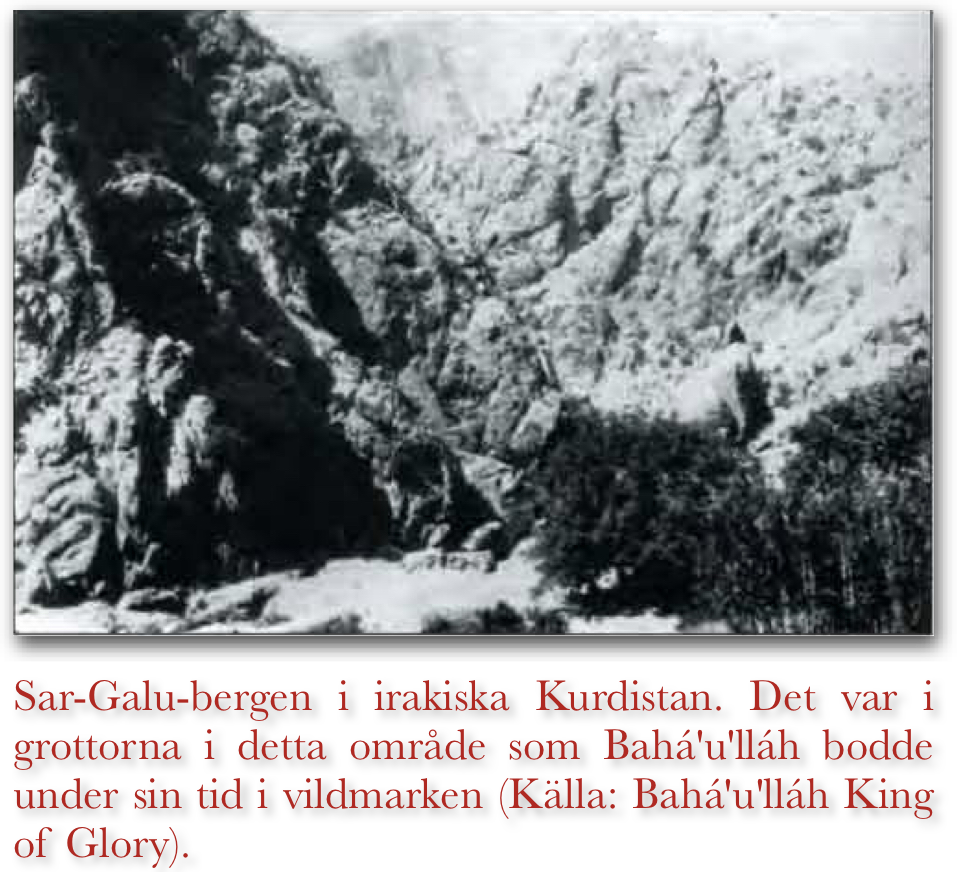

Prince Dolgorki encouraged Bahá'u'lláh to emigrate to Russia but the latter chose Iraq, probably for a number of reasons. For instance, Najaf and Karbilá, two major centers of Shí'ah pilgrimage, were located in Iraq.* Also, Iraq's vicinity with Persia (Iran) made it possible for Him to keep a close eye on the events in Persia and stay in touch with other active Bábís. In addition, the presence of a multitude of Shí'ahs in Iraq provided Him with fertile ground for spreading the teachings of the Báb in those regions.

A group of Bábís chose to follow Bahá'u'lláh into exile in 1853. Among them was His half-brother Mírzá Yahya, otherwise known as Subh-i-Azal (”Morn of Eternity”), whom the Báb had appointed to head the Bábí movement after His death. (* Islám, like Christianity, is divided into two major denominations, the Shí'ah sect being centered in Iran and the Sunní sect in Iraq. The recent conflict between the two countries was due in part to this division, much as was the case in the wars between the Catholics and Protestants in Christian Europe several centuries ago.)

Bahá’í accounts claim that the Báb's appointment of Azal (who was thirteen years younger than Bahá'u'lláh) was only nominal, as he was only in his teens at that time. The purpose behind this was to divert the attention of the opposition from Bahá'u'lláh, the Promised One of the Bábí dispensation, Whose rising prominence was endangering His life.

The arrangement was suggested by Bahá'u'lláh to the Báb, Who approved it. Beside Bahá'u'lláh and the Báb, only two other individuals, Mírzá Musá (Aqáy-i-Kalím), Bahá'u'lláh's full brother, and a certain Mullá Abdu'l-Karím-í-Qazvíní, who was later martyred in Tehrán, were aware of this arrangement. However, following the Báb's martyrdom, the question of succession came to cause much disturbance among the faithful. It ultimately came to result in a permanent rift between Bahá'u'lláh and Azal.

Azal's Leadership - en

While future historians may need to further clarify the exact nature of Azal's nomination, there is little doubt at this time that, following the Báb's execution in 1850, the generality of Bábís came to regard Azal as the Báb's successor. At the time of the Báb's execution, Azal had gone into hiding in the mountains of Mázíndarán and later managed to flee Persia and join Bahá'u'lláh's family in Baghdád a few months after the arrival of the latter in 1853. The events transpiring in Baghdád during the next few years indicate that Azal was not a particularly effective leader.

Bahá'u'lláh and Azal were of significantly different temperaments and abilities. As a consequence, they had sharply contrasting leadership styles which soon became evident. Whereas Azal was normally withdrawn and retiring, Bahá'u'lláh was energetic and active. Understandably, those who came to support them had opposing views of the other leader's attributes. What Bahá’ís regarded as Azal's cowardice was to Azalis his caution as the surviving head of the movement, and what the latter considered Bahá'u'lláh's ambition was to Bahá’ís His love and concern for a community that, because the martyrdom of the Báb, was demoralized and disintegrating. Nevertheless, it is clear that Azal's continuous insistence to remain in hiding or seclusion was the last thing a struggling community needed.

Smith, Peter. The Bábí & bahá’í Religions: From Messianic Shí'ism to a World Religion, Cambridge: The University Press, 1987, s. 59.

The severity of persecutions of early 1850's had driven the Bábís in Persia underground. Only the small community in Iraq could hope to preserve and spread the message of the martyred Báb. However, at this crucial juncture, Azal chose to distance himself from others. According to contemporary accounts, he changed his identity and appearance on several occasions and even threatened to excommunicate anyone who might reveal his identity or whereabouts.

His unforceful response did not sit well with many Bábís. Some saw no difference between the 'hidden Azal' and the Shíah's Hidden Imám.* Consequently, dissatisfaction with Azal's leadership began to mount. In the meantime, he continued to maintain the militant policy of the more radical elements of the Bábí movement and encouraged his supporters to, whenever appropriate, attack the ”hated” Shíahs and even went so far as dispatching an assassin for a second attempt on the life of Násirí'd-Din Sháh. In contrast to Azal's seclusive but radical attitude, Bahá'u'lláh began to actively encourage a pacific policy which became an attractive alternative to the more moderate Bábís. (* Shí'ah tradition holds that twelve Imáms, or holy leaders have appeared since the time of Muḥammad. According to tradition, the twelfth and last of these Imáms wandered into a cave and was never seen again. The Shí'ahs believe that, like Elijah, this ”Hidden Imám” would one day reappear. The name 'hidden Azal' was used by some as a callous joke.)

In view of the disasters of early 1850's, Bahá'u'lláh supported a conciliatory attitude toward others and pushed for major reforms in the character and behavior of the Bábís. He even attempted what to radical Bábís was the unthinkable rapprochement with the Persian government and its representatives in the Ottoman Empire—the same government they held responsible for the execution of the Báb and fierce persecution of their fellow-believers. This policy shift was welcomed by some but incurred the wrath of Azal and those who were content with the status quo. It also contributed to the growing polarization within the ranks of Bábís over the next few years.

In the meantime, while Azal continued to be reclusive, Bahá'u'lláh began to write proliferately and remain publicly visible and easily accessible to those who turned to Him for guidance and leadership. He also showed marks of a competent leader by establishing an organized network of communication which linked the fragmented communities of Persia and Iraq. Under His supervision, the Bábís of Persia would travel to Iraq, if necessary in the guise of Shí'ah pilgrims, bring Him letters and questions from other believers, and depart with His replies. He also had couriers assigned specifically to undertake such travels and visit the local communities en route, thus bringing together various communities and groups. Ultimately, this network seems to have succeeded in reviving the cohesiveness of the Bábís as a religious group and significantly contributed to ascendancy of Bahá'u'lláh over Azal. It also generated a loyal band of followers for Bahá'u'lláh inside Persia who, by their partisanship, tended to devalue the overall status and leadership abilities of Azal.

Concurrently, inside Persia some well-known Bábís began to show discontent with Azal's leadership. Others found his writings uninspiring and severely inadequate and began to challenge his authority. A few went so far as refuting his claims to successorship, advancing counter-claims, and disseminating their own writings.

Still others began to turn to Bahá'u'lláh for spiritual guidance. One such individual was Hájí Mírzá Kamálu'd- Dín-i-Naráqi who initially asked Azal to enlighten him on the Qur'ánic verse ”All food was allowed to the children of Israel except that which Israel made unlawful for itself.” Azal wrote a commentary on this verse which Naraqi apparently found inadequate. The latter then presented the same question to Bahá'u'lláh. In response, Bahá'u'lláh wrote what is today known as the Tablet of All Food (or ”Lawḥ-i-Kullu't-Tá'am”).

The Tablet of All Food - en

The presence of ”hierarchies” or ”degrees” of existence in the universe may be foreign to some readers. Bahá’ís believe the existence of such hierarchies are an essential prerequisite for the appearance of order and perfection in all the worlds of God, including this world. ”For existing beings could not be embodied in only one degree, one station, one kind, one species, and one class....”

‘Abdu'l—Bahá, Some Answered Questions, s. 129.

‘Abdu'l-Bahá expounds that, in this world, the essential hierarchy of existence is manifested through the appearance of the mineral, vegetable, animal, and human kingdoms (vertical degrees of difference). By the same token, one can observe the existence of such differences in the degrees of perfections among the members of the same kingdom (horizontal differences). Similar hierarchies are imperative for the appearance of order and perfections in the afterlife.

For more information, refer to ‘Abdu'l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions, ff. 129-131 and ff. 235-236.

In the Tablet of All Food, which is penned in a highly mystical language,* Bahá'u'lláh states that there are many spiritual worlds in the next life, and the above-mentioned Qur'anic verse has infinite meanings in each of these worlds most of which man could not comprehend in this earthly life. He then proceeds to identify four such worlds and describe some of the meanings of certain words in the verse.

An example of this is found in His examination of the mystical significance of the word ”food”. He notes that, at the highest spiritual level, it signifies the throne of ”Háhút” (Divine Oneness) where God's unapproachable Essence exists. This is a world which is completely beyond human understanding and even the prophets have no access to it. (* The style of Bahá'u'lláh's writing was incomparable in its range and was specifically tailored to the capacity of the reader. Works such as the Tablet of All Food and The Seven Valleys were written in a style familiar to readers from a mystically oriented Sufi background.)

The word Háhút is constructed according to the same pattern as similar Arabic words with spiritual connotations such as Láhút (divinity). Its meaning is probably based on the first letter Ha, which stands for ”Huwiyyah” (God's self-identity). The following description of God from one of Bahá'u'lláh's writings perhaps best fits the world of Háhút.

Cole, Juan R. ”Bahá'u'lláh and the Naqshbandi Sufis in Iraq.” In Cole, Juan R. & Moojan Momen, From Iran East & West: Studies in Bábí and bahá’í history. Los Angeles: Kalimat Press, 1984, ff. 12-13

”From time immemorial, He, the Divine Being, hath been veiled in the ineffable sanctity of His exalted Self, and will everlastingly continue to be wrapt in the impenetrable mystery of His unknowable Essence...”

Next in the hierarchy of spiritual worlds is the world of Láhút (Divinity) which He describes as the ”Heavenly Court.” This realm is ”perhaps the world of God in relation to His Manifestations and Chosen Ones” where His omnipotence drives the prophets to pronounce their utter nothingness in relation to Him. The well-known Qur'anic verse ”He is God, there is no God but Him” may well apply here. The world of Láhút emphasizes God's unity and uniqueness. Only the most purified souls could understand this world.

The next lower world is Jabarút (Divine Dominion), where prophets and chosen ones are allowed to use theophanic language and identify themselves with God ”on the level of His attributes.” They can identify themselves closely with God, claim unity with Him, and speak with His voice and authority. The realm of Jabarút seems to be the plane of prophets and chosen ones in relation to the world of creation:

”When I contemplate, O my God, the relationship that bindeth me to Thee, I am moved to proclaim to all created things verily I am God!”

The realm of Malakut (Divine Power or Kingdom) is next, described by Bahá'u'lláh as the ”Heaven of Divine Justice” inhabited by souls who have detached themselves from the riches of the material world. In addition to these worlds, Bahá'u'lláh identifies another world as Nasut (physical beings) which is the lowest in the hierarchy and is defined as the ”Heaven of Bounty.” Compared to the other worlds, the world of Nasut is in a state of subsistence because it has come to existence and continues to exist only through God's ”bounty.” Bahá'u'lláh states that should this bounty be replaced, even for a moment, with God's ”justice” the world of Nasut would completely cease to exist.

The exquisite beauty and insight of this Tablet left no doubt in the mind of Naraqi as to Whom he should follow. Bahá'u'lláh read this commentary to Naraqi, but did not give it to him. While it is not precisely known why He did so, His purpose may have been to avoid further hostilities between Himself and Azal and greater divisions among the faithful. Nevertheless, Naraqi evidently was so impressed with Bahá'u'lláh's explanation that he immediately pledged allegiance to Him. The news of this event further damaged Azal's credibility and increased Bahá'u'lláh's popularity.

Azal's Reaction - en

Azal was alarmed by the rising prestige of his half-brother. He was also becoming disheartened by the growing number of defections and opposition from well-known figures in the movement. Therefore, aided by a close companion, Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfáhání (referred to by the Guardian as, ”the Antichrist of the Bahá’í dispensation”), he initiated an organized campaign to regain his credibility. This involved, among other things, efforts to discredit Bahá'u'lláh and represent Him as someone who was attempting to ”usurp” his position.

Bahá'u'lláh, in His turn, was becoming increasingly saddened by those in the community who were spreading rumors against Him and who failed to see the clear indications of His superior knowledge and ability as well as His sincere concern for a disunified community. Soon His close associates began to observe in Him signs of pending withdrawal. His attendant, Mírzá Aqa Jan, heard Bahá'u'lláh refer to those who considered themselves to be His enemies shortly before His retirement, likening them to the unfaithful of the past who, ”...for three thousand years have worshiped idols, and bowed down before the Golden Calf.” Now, too, they are fit for nothing better. ”What relation can there be between this people and Him Who is the Countenance of Glory? ”What ties can bind them to the One Who is the supreme embodiment of all that is lovable?”

Effendi, Shoghi. God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois: bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1979, s. 119

Retirement to Kurdistan - en

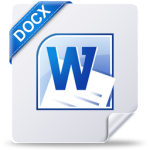

On the morning of April 10th, 1854, to their utmost surprise, Bahá'u'lláh's household awoke to find Him gone. He had left Baghdad for the mountains of Sulaymáníyyih in the heart of Kurdish Iraq.

In one of His later writings, He thus explained His reason for leaving Baghdad:

”The one object of Our retirement was to avoid becoming a subject of discord among the faithful, a source of disturbance unto Our companions, the means of injury to any soul, or the cause of sorrow to any heart.”

Abu'l-Q'asim-i-Hamadani, a Muslim, was the only person who accompanied Bahá'u'lláh from Baghdad and remained aware of His whereabouts in Kurdistan. Evidently, Bahá'u'lláh gave this individual a sum of money and instructed him to act as a merchant in that region. Hamadani occasionally visited Bahá'u'lláh and brought Him money and certain goods. Bahá'u'lláh who was intent upon living a life of complete solitude decided to conceal His true identity by dressing in the garb of a poor dervish and assuming the fictitious name of Darvísh Muḥammad-i-Irani. He only took with Himself one change of clothes and an alms-bowl or kashkul which is typically carried by dervishes. (Bahá'u'lláh's kashkul is preserved in the Bahá’í International Archives at Haifa, Israel.)

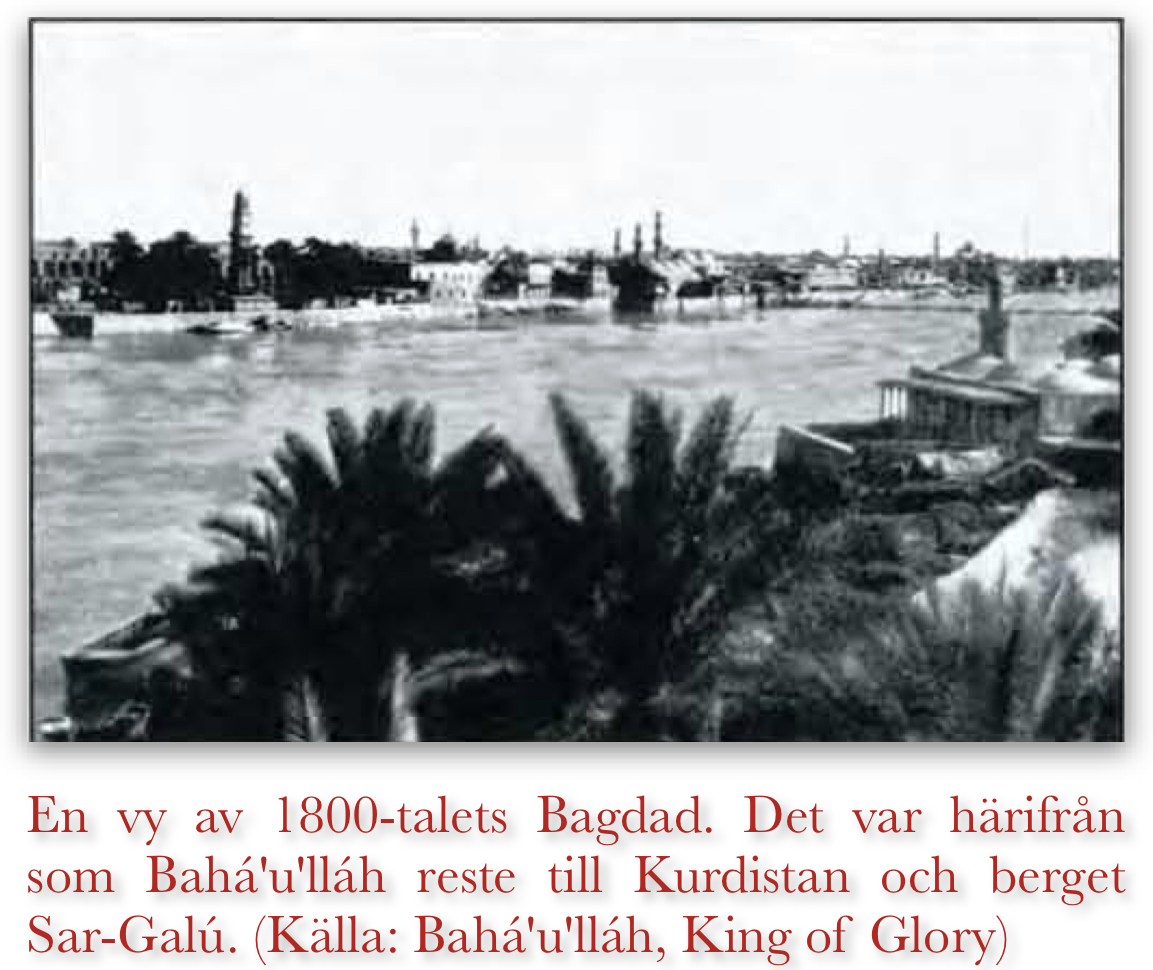

In the first phase of His retirement, He lived on a mountain named Sar-Galu, about 3 days of walking distance from Sulaymáníyyíh in the Iraqi Kurdistan. Milk and rice were His main sources of sustenance there, which He evidently obtained by occasionally traveling to nearby towns. His dwelling place was sometimes a cave and at other times a rude structure of stones that was also used as shelter by peasants who, twice a year (during planting and harvest), traveled to that area.

It is not entirely known how Bahá'u'lláh's days were spent in Sar-Galu. Some Bahá’í accounts suggest that He was going through the same purification process which all prophets must go through before revealing their mission. Thus, He is believed to have been mostly engaged in writing and chanting prayers in the wilderness and reflecting upon the events that had transpired and possibly what the future had in store.

One thing is, however, clear. He was extremely distressed during this period. In a letter to His cousin Maryam, written after His return to Baghdad, Bahá'u'lláh stressed His utter loneliness in Sar-Galu by stating that His only companions in those days were the 'birds of the air' and the 'beasts of the field.' Additionally, in the Kitab-i-Iqan which He wrote later, He described His state of mind in that region as follows:

”From Our eyes there rained tears of anguish, and in Our bleeding heart there surged an ocean of agonizing pain. Many a night We had no food for sustenance, and many a day Our body found no rest. Alone, We communed with Our spirit, oblivious of the world and all that is therein....”

For some time, Bahá'u'lláh was successful in completely severing ties with the outside world, but this did not last long. Either the travelers who passed through or the migrant farm workers who visited the Sar-Galu mountains must have come into contact with Him or observed Him living a life of asceticism which was favored by the mystics (Sufis) who resided in those regions and related their observations to others. Consequently, through word of mouth, His fame as a detached Soul who had chosen to live in wilderness and eschewed human society began to spread to neighboring towns.

Shortly thereafter, Shaykh Isma'il, the leader of the mystic Naqshbandi Sufi group, came into contact with Bahá'u'lláh. It is not known how the two first met. What is clear, however, is that soon the Shaykh developed an attachment to Bahá'u'lláh and, over time, persuaded Him to leave Sar-Galu and take residence in his seminary (or takyah) in the city of Sulaymáníyyih. Bahá'u'lláh's stay in Sar-Galu lasted less than a year, from April of 1854 to sometime in 1855, although the exact date and circumstances of His departure from Sar-Galu remain unknown.

Around the same period new developments took place in Baghdad and Persia which were indicative of further radicalization of Azal and his supporters. Some of the more learned Bábís who had found Azal's leadership wanting began to challenge him by advancing counterclaims to leadership and disseminating their own writings. It is believed that at one time, as many as twenty-five individuals had advanced some type of claim to spiritual authority. Among them were Mírzá Assad'u'llah-i-Khuy surnamed Dayyán (Judge) by the Báb and Nabil- i-Zarandí (the author of The Dawn-Breakers).

Probably the most serious challenge came from Dayyán. His threat became even more serious when a cousin of the Báb, Mírzá ‘Alí-Aḳbar, began to openly support him and to defy Azal. The latter felt so threatened by this new development that he first condemned Dayyán in one of his books ”The Sleeper Awakened” (or ”Mustayqiz”) and then sentenced both him and the Báb's cousin to death.

Mírzá Muḥammad-i-Mázandarání, a devoted follower of Azal, set out for Persia to carry out the sentence, but Dayyán could not be found in his native Ádhirbayján. Shortly after Bahá'u'lláh's return from Sulaymáníyyíh, however, the assassin succeeded in completing his mission by murdering both Dayyán and the Báb's cousin in Baghdád. Before Bahá'u'lláh's return, and to the dismay of many, Azal also forcibly married the Báb's widow in Iraq. When Bahá'u'lláh later learned of this union, He severely censured it. Azal's main motive in entering this marriage may have been to enhance his credibility as the Báb's rightful successor. Later, he even allowed his chief accomplice, Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfáhání, to marry the same widow. For the time being, however, Bahá'u'lláh remained unaware of these developments. He had recently started the second phase of His self-imposed exile in Sulaymáníyyíh.

As the vast majority of Bábís came from Muslim backgrounds, many of them tended to retain the traditional Muslim attitudes towards women as property. In Azal's case, he had obviously ignored the impropriety of these marriages. Fortunately, the widow of the Báb was to eventually be placed under the protection of Bahá'u'lláh and to be rid of the machinations of Azal and his followers.

Sulaymáníyyih - en

At the time of Bahá'u'lláh's seclusion Sulaymáníyyih was a town of about 6,000 inhabitants, the majority being Sunní Kurds. This group was hostile toward Muslims of Shí'ah background (such as Persians) whom they regarded as seceders from Islám. Nevertheless, Bahá'u'lláh seems to have been quickly accepted and respected by the local people. This may have been due to His attire and lifestyle as a dervish and the reverence that the venerable Shaykh Isma'il displayed toward Him by personally inviting Him to the town.

For a short while, no one suspected Bahá'u'lláh to be possessed of any wisdom or learning. However, this did not last. One day, a student of Shaykh Isma'il who attended to Bahá'u'lláh's needs, accidentally came upon a specimen of His calligraphy — an art which Bahá'u'lláh, like most children of nobility in Persia, had learned in childhood. His penmanship was of such high quality that it took the student by complete surprise. He decided to show it to his instructors and fellow students. The seminary was also bewildered. They had not expected such penmanship from an uneducated hermit. Examples of Bahá'u'lláh's writing style soon became available in town through His correspondence with certain Sufi leaders in the area. Thus, His true identity and aristocratic past soon became known to the Naqshbandi mystics as well as the general populace.

Life Among the Sufis - en

The Naqshbandi order was originally founded in Central Asia by Bahá'u'd-Din Muḥammad-i-Naqshbandi (1317-1389 A.D.). Later, the order broke into two main factions. One was the Mujaddidiyyah order which was established by an Indian thinker, Ahmad-i-Sirhindi (1564-1624 A.D.), and which flourished in India. The other was the Khaledíyyíh order which was founded by ‘Abdu'l-Bahá Diya'u'd-Din Khalid-i-Sháhrizuri (d. 1827) and which spread in Iraq and Syria.

Sirhindi, a Muslim elite, vehemently opposed the religious laxness he observed in the thinking of most converts from Hinduism to Islám in India. He advocated strict observance of Islámic laws. He also wrote extensively against both Shí'ism and Hinduism and rejected the doctrine of ”existential monism” (Wahdat al-wujud) which was promulgated by the renowned Muslim mystic Ibn-i-Arabi.

Detta är en tro att Gud är en del av människan och att det inte finns någon skillnad mellan den gudomliga, mänskliga och materiella världen.

He attacked attempts by some Indian Muslims to reconcile Ibn-i-Arabi's idea of existential monism with the Vedantic school of Hinduism, which held that the ultimate goal of one's spiritual destiny was complete ”physical” reunion with the essence of Brahma (God). Ultimately, his ideology came to have great impact on the rest of the Muslim world. Sirhindi also advanced certain claims. For instance, he claimed to be the Qayyum (the Herald of the Qa'im or Promised One); the Perfect Man who acted as God's intermediary among the faithful.

Detta är en tro att Gud är en del av människan och att det inte finns någon skillnad mellan den gudomliga, mänskliga och materiella världen.

Shaykh Khaled-i-Sháhrizuri, a native of Iraqi Kurdistan, was among the thinkers whose line of thought were influenced by Sirhindi. Around 1811 to 1812, he traveled to Sulaymáníyyih and spread His teachings in that region. Like Sirhindi, Khaled also claimed to possess supernatural or mystical powers. His influence lives on to this day in Sulaymáníyyih and Baghdád as well as in Damascus, Syria, where he spent the last seven years of his life. Following Khaled's death, the Naqshbandis in Kurdistan began to refer to themselves as the Khaledíyyih (followers of Khaled) and call Shaykh Khaled by the surname Mawlana (”our lord”).

The Bábís and Naqshbandis represented two distinct reformist trends in the nineteenth-century Middle East. They both favored elimination of non-revelatory accretions to the pure Faith of Muḥammad. For instance, the tradition of blind imitation (Taqlid) practiced by Shi'ahs was attacked by both groups as was the doctrine of existential monism. Therefore, the Khaledis should have readily accepted many of Bahá'u'lláh's theological interpretations. However, the Bábís and Naqshbandis disagreed as to the extent of reforms needed in Islam. While the Naqshbandis were content with certain theological and ritual reforms within a strictly Sunní school of Islam, the Bábís were convinced that nothing short of the messianic advent of the Promised Mahdi in the person of the Báb could remedy the ills of Islám and of mankind in general.

Shortly after the true identity of Bahá'u'lláh was revealed, the Khaledi seminary became engaged in the study of Meccan Victories (Al-Futuhat al-Makkíyyah), the well-known work of the renowned mystic thinker Ibn-i- Arabi. In response to a request, in the course of several interviews, Bahá'u'lláh answered the seminary's questions regarding certain abstruse passages in this book and even made corrective remarks concerning some of Abn-i-Arabi's beliefs. For example, He may well have objected to Arabi's advocacy of the doctrine of existential monism. The Khaledis perhaps readily accepted His assertions as they themselves believed in the eventual spiritual (as opposed to physical) reunion of man with his Creator.

Shaykh Isma'il, the Khaledi leader, evidently was impressed enough by Bahá'u'lláh's comments to request that He compose an ode (or qasidah) in the same style as a famous mystic work, Ibn-i-Farid's Poem of the Way (or Nazmu's-Suluk). Bahá'u'lláh complied with this request and wrote a very long poem of some 2,000 verses, but He chose to preserve only 127 of those verses and destroyed the rest of the poem, presumably because they expressed His messianic feelings too forcefully. Today this work is known among Bahá'u'lláh's faithful as the Poem of the Dove (or Al- Qasidah-al-Warqa'iyyah).

In this poem, Bahá'u'lláh displays the ability to express Bábí theological beliefs in Sufi terminology. This is not surprising, however, in view of the fact that Sufi works were popular in Persia and, over the centuries, had left a lasting impact on the culture and literature of that country. Persians of nobility, such as Bahá'u'lláh, were raised on such Sufi classics as Rumi's Mathnawi and Attar's The Speech of the Bird (or Mantiqu't-Tayr). Moreover, Sufism had experienced a revival in 19th century Persia and was highly favored in the court circles which included the family of Bahá'u'lláh.

Also, Sufi expressions which emphasized personal transformation of character enabled Bahá'u'lláh to richly describe His doctrine of spreading Bábísm through the force of example rather than militancy, as had been the case with the supporters of earlier religions. He continued to use this mixture of Bábí and Sufi terminology until the period preceding the year of the public declaration of His Station in 1863, during which time He gradually began to adopt a distinctly different style. In addition to the Poem of the Dove, Bahá'u'lláh wrote several works of note with highly mystical flavor before 1863. Among these were the Hidden Words, the Seven Valleys, the Four Valleys, and the Book of Certitude (or Kitáb-i-Iqán).

Even though there are similarities in both style and content between Bahá'u'lláh's Poem of the Dove and Ibn-i-Farid's Poem of the Way, there are also significant metaphysical and theological differences between the two. For instance, in the course of his poem, Ibn-i-Farid, who adhered to existential monism, claimed to have physically seen the ”Essence” of the Beloved (God) and ultimately, through a chain of events, experienced moments of reunion with Him. Bahá'u'lláh does not make such a claim anywhere in His poem, as God's essential nature is beyond human comprehension. Instead, He employs messianic themes and refers, in veiled language, to an exalted station of Prophethood for Himself, which Ibn-i-Farid does not.

Bahá'u'lláh's Return to Baghdád - en

The exact circumstances surrounding Bahá'u'lláh's return from Sulaymáníyyíh are not entirely clear. It is known that late in 1855, Hamadani, Bahá'u'lláh's Muslim companion, was returning from Persia and heading to Sar-Galu with some goods for Bahá'u'lláh, but was attacked by thieves and fatally wounded. Before his death, he bequeathed all his possessions to the mysterious Darvísh Muḥammad-i-Irani. About the same time, reports of a mysterious darvish from Iran had begun to reach Baghdád. Hamadani's death left little doubt for Bahá'u'lláh's family as to the true identity and whereabouts of Darvísh Muḥammad, since the former had also disappeared in Baghdád at about the same time as Bahá'u'lláh two years previously. They rightly concluded that the mysterious dervish must be none other than Bahá'u'lláh Himself.

At this time, in the absence of effective leadership, the morale of the Bábí community had deteriorated considerably, much as was the case with their ancient counterparts during the absence of Moses. This decay caused such stress for the family of Bahá'u'lláh that they finally convinced His brother Mírzá Musá to try to find Bahá'u'lláh and ask for His return. Thus, Mírzá Musá requested his Arab father-in-law, Shaykh Sultan, to locate Bahá'u'lláh and bring Him back to Baghdád. Even Azal now wanted his half-brother to come back, though it is not clear why. Perhaps, in light of the growing number of defections and rival claimants, he felt Bahá'u'lláh might be willing to lend some of His prestige to his sagging leadership.

Azal's supporters, true to form, offered a different interpretation of the events that led to Bahá'u'lláh's return, trying to convince others that Bahá'u'lláh left Sulaymáníyyíh in 1856 at the command of Azal. They also maintained that Bahá'u'lláh considered Himself to be under Azal's authority. This, however, is clearly false, as is demonstrated by such works of Bahá'u'lláh as the poems Rash-i-Ama (Sprinkling of Essence) and Al-Qasidah-al-Warqa'iyyah (Poem of the Dove), which were produced around the time He received His Revelation.

The first of these two poems is perhaps the earliest of Bahá'u'lláh's known works; penned in 1853 in the dungeon in Tihrán known as the ”Black Pit”. Together with the second poem, the two provide irrefutable evidence that Bahá'u'lláh had messianic expectations and had received supernatural intimations long before He returned to Baghdád.

It is assumed that His return from Sulaymáníyyíh was due to such factors as the plight of the leaderless Bábí community of Baghdád. He Himself seems to have taken Shaykh Sultan's mission as a sign that God wanted Him to return.

It took Shaykh Sultan and a companion approximately two months before they located Bahá'u'lláh in the vicinity of Sulaymáníyyih. After a while, Bahá'u'lláh consented to depart for Baghdád, where He arrived in March 19, 1856. His stay in Kurdistan took exactly two lunar years.

Den kalender som används i muslimska länder är baserad på ett antal månens banor runt jorden, till skillnad från den västerländska kalendern som är baserad på jordens bana runt solen. Detta medför att den muslimska kalendern är kortare än den som används i västvärlden.

Following His return, Bahá'u'lláh maintained correspondence with some Sufis in Kurdistan. Two of His well-known works were written in response to questions posed by such individuals. The Seven Valleys was penned in reply to a query of Shaykh Muhyí'd-Dín, the judge of the town of Khániqayn in Kurdistan, and the Four Valleys was written in response to questions by Shaykh Abdu'r-Rahmán, the leader of the Qadiriyyih Sufis. He continued to be respected by many Sufis in Kurdistan long after His return and, even today, some of the inhabitants of Sulaymáníyyih still possess samples of Bahá'u'lláh's works with which they refuse to part at any price.

Bahá'u'lláh's return to Baghdád signaled the beginning of a new era in the Bábí movement. It initiated a period marked by His growing prominence as the head of the Bábí community and simultaneous decline in the fortunes of Azal. After a seven year span that witnessed a gradual but notable transformation in the character and attitudes of the community, in 1863, Bahá'u'lláh publicly declared Himself the Promised One. In a relatively short period of time, the faithful who resided in Persia and the neighboring regions gave allegiance to Him and became designated as Bahá’ís, or followers of Bahá.

Bahá'u'lláh och Naqshbandi Sufierna i Iraq, 1854-1856 - en

Many scholars have remarked upon the transformation of the nineteenth-century Bábí movement into the Bahá’í Faith, but few have attempted a close analysis of this process. The intellectual and social history of the Bábí religion in the decade of the 1850s remains largely unknown. This in spite of the fact that these years served as a crucial transition period between primitive Bábísm and the development from it of the Azali and Bahá’í movements. Pioneering scholars like E. G. Browne had little or nothing to say about these years owing to the dearth of primary sources dating from this time available to them. As we shall see below, some of what Browne did say is wrong, and his views need to be revised in the light of new evidence.

During the past two decades, Bahá’ís in Iran published works of great interest by Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alí of Nur, Bahá'u'lláh (1817-1892). One of these is a poem in ‘Arabic by the founder of the Bahá’í Faith entitled AI-Qaṣídah al-Warqá'iyyah (Ode of the dove), which he penned during his two-year sojourn (1854-1856) in Iraqi Kurdistan. The work synthesises Bábí and Sufi themes, and it represents one of the earlier statements of Bahá'u'lláh's mystical theology. The following analysis aims at analysis contributing to a better understanding of the earliest phase of the metamorphosis of Bábísm into the Bahá’í Faith.

See especially. volume IV of ‘Abdu'l-Ḥamíd Ishráq Khávarí's anthology, Má'idahy-i ásmání;(Tehran: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1963-4, nine vols.) and Bahá'u'lláh, Áthár-i qalam-i a'lá, III (Tehran: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 129 B.E./1972-73) for works composed in the 1850s and early 1860s.

Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alí, Bahá'u'lláh, the son of Mírzá ‘Abbas, was born in Tehran on November 12, 1817. His father, known as Mírzá Buzurg-i Núrí, was a native of Núr in Mazandaran and a minister in the royal court. The young Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alí received a private education which emphasised the Qur'an and Persian poetry and which aimed at preparing him for a career as a courtier. He refused, however, to follow his father into a court career. As the British scholar Denis MacEoin has pointed out, Bahá'u'lláh's sensitivity and pacific disposition manifested themselves in his distress as a youth on reading of the Muslim execution of the Banú Qurayẓah in the time of Muḥammad.

The most important primary source for the life of Bahá'u'lláh is the history by Muḥammad-i Zarandi, Nabíl-i-‘Aẓam the original of which has never been published. An autograph manuscript exists at the lnternational Bahá’í Archives in Haifa. From this a partial translation was made: The Dawnbreakers. trans. Shoghi Effendi (New York: Baha', Publishing Committee, 1932). Bahá'u'lláh's son, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá ‘Abbas, wrote a history which was edited and translated by E. C. Browne as A Traveller's Narrative (Cambridge: University Press, 1891). Popular but still useful secondary sources include Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh (Oxford: Ceorge Ronald, 2 vols., 1974-76) and the more scholarly work by H. M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory (Oxford: Ceorge Ronald, 1981).

See Denis MacEoin, The Concept of Jihad in the Báb, and Bahá’í Movements, unpublished ms., 1979, pp. 36-37, where he cites a passage in Ishráq Khávarí's, ed ., Má'idahy-i ásmání;, VII, p. 136.

In 1844, a young merchant in Shiraz named Sayyid ‘Alí Muḥammad declared himself to be the Báb, a figure in Shi'ih Islam through whom the hidden Twelfth Imam spoke. The Báb's first disciple, Mullá Ḥusayn-i-Bushrú’í, visited Tehran later that year and sent Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alí a messenger to inform him of the Báb's claims. This mission succeeded, and the young Mírzá entered the ranks of the Bábís. Why Mulla Ḥusayn, or perhaps even the Báb, singled out Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alí for this special attention remains obscure. Perhaps the almost Tolstoyan figure of this young nobleman who rejected worldly ambitions and engaged in philanthropic activities posed an irresistible challenge for the new religious movement. The Bábí movement developed out of a school of Twelver Shiism known as Shaykhism, so called after its founder Shaykh-Aḥmad al-Ahsá’í (d. 1826), which contained millenarian emphases. Many prominent Bábís were converts from Shaykhism which came under the leadership of Siyyid Kázim-i-Rashtí, al-Ahsá’í's successor, but this does not seem to have been the case with the Núrí family.

Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alí quickly became a prominent figure in the Bábí movement, and increasingly played a low-key leadership role after the government's incarceration of the Báb in Azerbaijan in 1847. When the Báb declared himself the Qa'im, the messianic return of the Twelfth Imam, Bahá'u'lláh organised a conference of Bábí leaders in the hamlet of Badasht to publicise this claim and obtain a consensus about it. There, the Bábí disciple and poetess, Ṭahirah Qurratu'l-'Ayn, scandalised some of the faithful by casting aside her veil to symbolise the advent of a new dispensation. At this conference, Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alí took as his Bábí title the divine name Bahel' (Splendor), In the late 1840s, fighting broke out between Bábís and Shí'ís in Mazandaran, Zanjan and Nayriz. Bahá'u'lláh was not present when government troops besieged the shrine of Shaykh Tabarsi in Mazandaran, where hundreds of Bábís had gathered, because Shí'í adversaries imprisoned him in the town of Amul. They at length released him, but they stripped him of at least some of his property.

Mírzá Ḥusayn Hamadání, The Táríkh-i-Jadíd, trans. E. G. Browne (Cambridge: University Press, 1893) pp. 241-244, For the background of these events see ‘Abbas Amanat's social-history analysis, The Early Vears of the Bábí Movement: Background Develop-ment, Ph. D. Diss. (Oxford 1981); and Denis M. MacEoin, From Shaykhism to Bábísm: A Study in Charismatic Renewal in Shi'i Islam, Ph .D. Diss. (Cambridge 1979).

The rapid spread of the Bábí movement with its millenarian overtones, and the opposition of the Iranian religious and governmental establishments it provoked, led to the temporary disruption of parts of Iran and the shedding of much blood – especially that of the Bábís, who as untrained civilians often ended up facing professional government fighting men. In a desperate bid to quell these disturbances, the Iranian government had the Báb shot in Tabriz on July 9, 1850. In revenge for this act a small splinter group of radical Bábís plotted the assassination of Nasiru'd-Dín Sháh. A Bábí named Ṣádiq Tabrízí and two accomplices carried out the attack on August I5, 1852, but it went awry when Tabrízí's gun misfired. The would be assassins were immediately arrested or dispatched, but this incident brought the entire Bábí community under suspicion. Many were brutally executed.

Bahá'u'lláh, recently returned from Najaf and Karbala in Iraq, was in Afcha near Tehran when the attempted assassination occurred. He realised that he would fall under suspicion as Bábí leader and surrendered himself to the authorities. They imprisoned him for four months, but at length found him innocent of any involvement with the plot. They nevertheless informed him that he would be exiled. While in prison a mystical experience convinced Bahá'u'lláh that he was destined to assume the leadership of the Bábí movement. He therefore chose to go into exile in Iraq, which was, though under Ottoman suzerainty, a major center of Shi'i pilgrimage from which he could keep in touch with events in Iran with relative ease. The government released him from his four-month imprisonment in the dungeon Siyah-Chál in December of 1852, and he set out for Iraq on January 12, 1853. The winter journey was a difficult one, and his party did not arrive in Baghdad until April 8.

Kazem Kazemzadeh and Firuz Kazemzadeh, Bahá'u'lláh's Prison Sentence: The Official Account," World Order, 13 (Winter, 1978-79) pp. 11-13.

A number of Bábís chose to follow Bahá'u'lláh into exile, including his half brother Mírzá Yaḥyá, Ṣubḥ-i-Azal, whom the Báb had appointed the titular head of the Bábí community. When Yaḥyá arrived later that year, the small Bábí community in Baghdad quickly became polarised, and a power struggle developed between Bahá'u'lláh and his younger brother. The death of the Báb, the government defeat of Bábí forces in Zan-jan, Mazandaran and Nayriz, and the persecutions of August-September 1852 in the wake of the assassination attempt-all this left the Bábís demoralised, divided and bereft of most of their leaders. Mírzá Yaḥyá tended to distance himself from the community, spending his time in disguise and dealing with affairs through proxies, including Bahá'u'lláh. There was wide-spread dissatisfaction with Yaḥyá's leadership, which apparently few took seriously. In the two years between the execution of the Báb and the persecutions in the summer of 1852, a great many claimants to the leadership of the Bábí movement emerged. Mírzá Yaḥyá at first refused to denounce these claims outright and so failed to stem the tide of schism. As his position deteriorated he became more desperate, however, and around 1856 he had one such claimant, Mírzá Asadu'llah Khu'í Dayyán assassinated.

Hamadání, The Táríkh-i-Jadíd, pp. 384-396.

Meanwhile, in the period 1853-1854, Bahá'u'lláh was apparently urging some reforms in view of the disasters of the previous four years, thus incurring the wrath of Bábís content with the status quo. Disheartened by the bickering among the Bábís in Iraq and wishing to avoid provoking yet another schism, he withdrew in the spring of 1854 to the mountainous wilder-ness of Sar Galu, around Sulaymaniyyah in Iraqi Kurdistan. Bahá'u'lláh took with him to Sar Galu a single servant, Abu'l-Qasim Hamadání, whom thieves later murdered. In the wilderness, Bahá'u'lláh lived the life of an ascetic holy man, eschewing human society, until his reputation for piety caused a local Sufi order to make contact with him. Shaykh Ismá'íl of the Naqshbandiyyah Khalidiyyah order successfully implored Bahá'u'lláh to come and reside in their takyah (seminary) in Sulaymaniyyah, at that time a mostly Kurdish town of about 6000.

For Bábí resistance to Bahá'u'lláh's reforms, see Hasht Bihisht, quoted in A Traveller's Narrative, II, pp. 356-357. For Algar's faulty chronology of this period, see Hamid Algar, Mírzá Malkum Khán : A Study in the History of Iranian Modernism (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1973). p. 58, where he wrongly says Bahá'u'lláh went to Kurdistan in 1859.

The Bábís and the Naqshbandis represented two very different reformist trends in nineteenth-century Middle Eastern society. They had in common a desire to slough off centuries-old accretions to the pure faith. But while the Naqshbandis were content with some theological and ritual reforms of a strict Sunni type of Islam, the Bábís were convinced that nothing less than the messianic advent of the promised Mahdi in the person of the Báb could remedy the ills besetting mankind. The Naqshbandiyyah has often been depicted (sometimes rather romantically and unhistorically) as the most important forerunner of twentieth-century trends toward a greater stress on the strict observance of ritual law in Islam. The emphasis on a return to the sources, careful adherence to the dictates of the revealed law, and communal solidarity against non-Muslims which characterise such modernist movements as the Salafiyyah were present to some extent in Naqshbandi Sufism long before the modern period.

The original order, founded by Baha'u'd-Dín Muḥammad Naqshband (1317- 1389 A. D.) in Central Asia, does not concern us here so much as two later branches of it. The first of these crystallized around the Indian thinker Aḥmad Sirhindí (1564-1624 A.D.), and was known as the Mujaddidiyyah. The other derived from ‘Abu'l-Bahá Diyá'u'd-Dín Khalid Sháhrizúrí (d. 1827) in Iraqi Kurdistan, and was called the Khalidiyyah .

Sirhindí, a member of India's urban, literate Muslim elite, reacted against the syncretism and religious laxness of the popular class converts to Islam from Hinduism. He also attacked the newly syncretic atmosphere at Akbar's court and insisted on greater conformity with Islamic law. He not only wrote polemics against Shiism and Hinduism, but he rejected the doctrine of existential monism (waḥdat al-wujúd) promulgated by the mystical school of Ibn ‘Arabi. Some Indian Muslims used the idea of existential monism to come to agreement with the Vedanta school of Hinduism. Sirhindí, following the medieval mystic Ala'u'd-Dawlah Simnani, claimed that the unity of the cosmos with God is not an objective fact with its locus in being, but a subjective experience with its locus in perception. He endeavored to replace the unity of being with the unity of perception (waḥdat ash-shuhúd).

See Shaykh-Aḥmad Sirhindí, Intikháb-i maktúbát, ed. and intro. Fazlur Raḥmán (Karachi: Iqbal Academy, 1968) and Badru'd-Dín Sirhindí, Ḥaḍarat al-quds (Lahore: Panjab Awqaf Department, 1971). For analysis see Saiyid Athar ‘Abbas Rizvi, Muslim Revivalist Movements in North India in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Agra: University Press, 1965) pp. 202- 313 and K. A. Nizami. Naqshbandi Influence on Mughal Rulers and Politics, Islamic Culture, 39 (1965) pp. 41- 52 .

The eighteenth-century Naqshbandi thinker Sháh Waliyu'lláh of Delhi also devoted himself to reform. While he did not op-pose the doctrine of existential monism, he did advocate a closer study of oral traditions attributed to the Prophet. He argued for more freedom for Muslim jurisconsults to practice individual interpretation (ijtihád) in arriving at Islamic legal judgments, attacking blind imitation (taklid).

Monism: Inom filosofin doktrinen att allt som existerar ytterst är av ett och samma slag. Neutral monism: Filosofisk uppfattning enligt vilken verkligheten är en konstruktion, baserad på sinnesupplevelsernas innehåll, vilka antas vara neutrala i den bemärkelsen att de varken är mentala eller materiella.

See Sháh Waliyu'lláh ad-Dihlawi, Hujjatu'lláh al-balighah, (Lahore: A1-Maktabah as-Salafiyyah, 1979, 2 vols.). 1:154-161 and Muḥammad Daud Rahbar, Sháh Walí ulláh and Ijtihad, Muslim World, 48 (1955) 346-358.

Not all Naqshbandi ideas in India would please twentieth-century Muslim reformers of the Salafí school. Sirhindí grandiosely claimed to be the renewer of Islam for the second Muslim millennium. He further announced that he was the Qayyúm, the Perfect Man through whom God's grace was mediated to the believers. He also downplayed the importance of some past Sufi saints. This caused him to be disliked by Sufis of a less iconoclastic stripe.

The reformist or revivalist ideas of the Naqshbandis in India had a wide impact on the rest of the Muslim world. In particular, Albert Hourani has insightfully demonstrated the influence that the Indian Mujaddidiyyah had on Shaykh Khalid Sháhrizúrí of Iraqi Kurdistan. Shaykh Khalid travelled to Syria as a young man, but soon returned to Kurdistan around the beginning of the nineteenth century. An Indian Sufi residing there, Mírzá Rahimu'llah "Darvísh Muḥammad", advised him to seek knowledge in India. Shaykh Khalid took the advice, and while in India he joined several Sufi orders, including the Naqshbandiyyah Mujaddidiyya. In Delhi, he studied with Sháh Waliú'lláh's son, ‘Abdu'l-‘Azíz Dihawí. He travelled through Iran on his way back to Kurdistan, engaging in heated debates with Shi'is which sometimes al most ended in violence .

E.g., John Voll, Muḥammad Ḥayya al-Sindi and Muḥammad ibn ‘Abdu'l-Wahháb: An Analysis of an Intellectual Group in Eighteenth Century Medina, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 38 (1975), pp. 32- 39.

Albert Hourani, Shaykh Khalid and the Naqshbandi Order, Islamic Philosophy and the Classical Tradition: Essays presented to R. Walzer (Colombia: University of South Carolina Press, 1972) pp. 89-103. See also, ‘Abdu'r-Razzáq al-Bíṭár, Ḥilyat al-bashar fí tátíkh al-qarn ath-thálith áshar (Damascus: Majma al-Lughah al-' ‘Arabiy-yah bi Dimashq, 1961) I: 570-587 and ‘Abdu'l-Majíd al-Khání, al-Ḥadá'íq al-wardiyyah fí haqá'iq ujalá' an-Naqshbandiyyah (Cairo: Dár aṭ- Ṭibá'ah al-‘Ámirah, 1308/ 1890, pp. 223 ff.

In 1811-1812 Shaykh Khalid was teaching in Sulaymaniyyah. He became embroiled in disputes with other local Sufi leaders, some of whom were Qadiri Shaykhs of the powerful Barzinji family. Aside from the rivalry between the Qadirí and the Naqshbandi orders, Hourani suggests two reasons for the hostility some showed to Shaykh Khalid. One may have been his uncompromising insistence on a strict application of the religious law in the face of popular practices among the Kurds. The other was the great following he gained and the extravagant claims he made to possessing mystical powers. The struggle climaxed in 1820, when Shaykh Khalid fled to Damascus after losing a contest for power with a Qádirí leader. He lived in Damascus the last seven years of his life and died there of the plague in 1827.

Hourani. Shaykh Khálid. p. 96; al-Biṭar. Ḥilyat al-bashar, 1; 580.

Shaykh Khalid's influence lived on in Damascus, Sulaymaniyyah and Baghdad. The Naqshbandi Sufis in Kurdistan increasingly referred to themselves simply as the Khalidiyyah, and called Shaykh Khalid Mawláná (our lord). Members of several important families in Kurdistan became Khalidí Naqshbandis. The Sufi Shaykhs in Kurdistan seem to have grown in power as the local civil institutions became increasingly disrupted. In 1842 Maḥmúd Pasha, the local dynastic chief of the Bában family, submitted to the invading forces of Qajar Iran. In 1847, Iran gave up claims to Sulaymaniyyah and the district around it in favor of the Ottoman Turks. In 1850, the Turks deposed the last of the Bában rulers, ‘Abdu'llah Pasha, preferring to rule Kurdistan more directly. In the midst of this political instability, the Sufi orders may well have provided a primary means of social integration .

Baban: Det var ett kurdiskt furstendöme som existerade från 1500-talet till 1850, med centrum runt Sulaymaniyah. Innan den sista Baban-ledaren avsattes 1850 hade deras styre begränsats till huvudstaden Sulaymaniyah och några få omkringliggande byar.

V. Minorsky. "Sulaimanfya." Encyclopaedia of Islam. 1st ed. (London; Lu'ac and Co. 1934) 3:537.

Hourani, Shaykh Khalid p. 99. See Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh. p. 124n for Bahá'u'lláh's relations with ‘Abdu'lláh Pasha Bábán in Baghdad. Balyuzi's identification of a Sayyid Dá'údí with the Khalidi Naqshbandi Dá'údí al-Baghdádí is tenuous. For al-Baghdádí, see ‘Umar Riḍá Kaḥḥalah. Mu'jam al-mu'allifín (Damascus; Taraqqi Press. 1957). 4:136-137.

The same paradoxical mixture of reformism and messianic claims which characterized such neo-orthodox Sufi movements as the Naqshbandis also typified Shaykhism and early Bábísm. Bábís, for instance, tended to attack blind tradition (taqlíd), as did Sháh Waliyu'llah. Denis MacEoin has shown that in its early years Bábísm acted as a call to return to a stricter practice of the Islamic law (sharí’ah) among Iran's Twelver Shi'is. This was, of course, before 1848-1850 when the Báb publicly claimed to be the Mahdi and revealed a new sharí'ah. The Shaykhi-Bábí tradition criticized many aspects of popular Sufism, and, like Sirhindí, rejected the doctrine of existential monism (waḥdat al-wujúd). Though Naqshbandis tended to show hostility to Shi'is, they often had a positive attitude toward the Twelve Imams, such that Bahá'u'lláh's often very Shi'i diction in this regard would not necessarily have offended them.

See e.g . Bahá'u'lláh, Haft vádí, Áthár-i qalam-i a'lá, Ill. p. 96; Eng. trans. by ‘Alí Kuli Khan and Marzieh Gail. The Seven Valleys and the Four Valleys (Wilmette. 111.; Bahá’í Publishing Trust. 1971) p. 5.

See Denis MacEoin, From Shaykhism to Bábísm, chapters 5 and 6.

For the major motifs in the Bábí-Bahá’í movement, see Peter Smith. "Motif Research: Peter Berger and the Bahá’í Faith," Religion, 8 (1979) pp. 210-34 .

Existentiell: Frågor som rör liv och död.

Hamid Algar, "Some Notes on the Naqshbandi Tariqat in Bosnia." Die Welt des Islams. N .S. vol. XIIl (1971 ) p. 194 .

The Khalidí Sufis knew Bahá'u'lláh, their guest, only as Darvísh Muḥammad-i Irání and believed him to be a recluse. Perhaps they thought his presence among them would bring some barakah (blessings). Gradually, however, Bahá'u'lláh's aristocratic bearing and culture began to betray him as something more than a mountain hermit. When the Sufis caught sight of his superb calligraphy one day, they became convinced that their guest was a man of refinement and learning. They asked him to comment on the texts they were studying in their group sessions.

Bahá’í sources state that Khalidís were then studying Ibn ‘Arabi's Al-Futúhát al-Makkiyyah (Meccan victories) and that Bahá'u'lláh not only gave a commentary on some pages, but corrected certain of the great Andalusian mystic's views. It may well be that he objected to Ibn ‘Arabi's ideas on existential monism. The Naqshbandi Sufis might have accepted any such reservations on this score, as this order often held that unity lies in experience or perception, not in being. In a treatise written three or four years later for Shaykh Muḥy'd-Dín, the magistrate (qáḍí) of Khániqayn in northeastern Iraq, Bahá'u'lláh stated that in the seventh valley, wherein the seeker attains the extinction of the base ego (faná), one transcends the stages of both waḥdat al-wujúd and waḥdat ash-shuhúd, of both existential and experiential monism . This is evidence that Bahá'u'lláh knew of the Simnání-Sirhindí doctrine, and felt that it too was ultimately inadequate in describing the relationship between God and the realized devotee. In any case, Bahá'u'lláhs critique of existential monism from the Shaykhi-Bábí tradition was just one level on which Naqshbandi and Bábí reformism may have met and found each other congenial.

Bahá'u'lláh, Haft vádí, Áthár-i qalam-i a'lá; Seven Valleys, p. 39.

Shaykh Ismá'íl, then a leader of the Khalidiyyah order in Sulaymaniyyah, was impressed enough by Bahá'u'lláh's comments on Ibn ‘Arabi's book to request that he compose an ode (qasfdah) in the meter and rhyme of Ibnu'l-Fáriḍs Poem of the Way (Naẓmu's-sulúk). Bahá'u'lláh complied with this request and produced a long poem of some 2000 verses. Of these, he chose out 127 which became known as Al-Qaṣldah al-Warqá'iyyah. Bahá'u'lláh may have discarded so many of the verses because they expressed too openly and forcefully the messianic feelings he had had since his imprisonment in the Sháh's dungeon. In any case, while Bahá'u'lláh's poem has many similarities to Ibnu'l-Fáriḍs mystical opus, the millenarian emphases of Bábí doctrine clearly dominate it. The fusion of Sufi mysticism with Bábí theological and eschatological teachings constitutes one of the most fascinating features of this work.

Umar ibn ‘Alí Ibnu'l-Fariḍ (1181-1235 A.D.) was an Egyptian mystic who spent some twenty years in the Ḥijáz. For his classic "Nazm as-Suluk." see A. J. Arberry. ed., The Mystical Poems of Ibn al-Fari" (London ; E. Walker, 1952); and A. J. Arberry. trans ., The Poem of the Way (London ; E. Walker. 1952); for Ibnu'l-Farid's thought. see R. A. Nicholson. Studies in Islamic Mysticism (Cambridge at the University Press. 1921); Muḥammad Mustafa Ḥilmí, lbnu'l-Farids wa'l-ḥubb al-iláhí (Cairo; Dar al-Ma'-Arif. 1971); and Issa J. Boullata. Verbal Arabesque and Mystical Union; A Study of Ibn al-Fariq's 'Al-Tá'iyya al-Kubrá ... Arab Studies Quarterly, 3 (Spring 1981) 152- 69.

Unfortunately, no scholarly edition of Bahá'u'lláh's Qaṣídah exists. It has been printed twice in Tehran, though (as the variants show) from two different manuscripts. No information about the manuscripts was provided by the editors. This writer has in his possession, in addition, a photocopy of yet another manuscript of the poem in the hand of the Bahá'u'lláh's amanuensis Zaynu'I-Muqarrabin. However, it has no colophon, and is probably rather late. It does, however, seem to be superior to either of the printed versions. The variants between these versions of the poem are not so numerous or important as to prevent us from grasping with some certainty the main outlines of the work.

For this episode. see Balyuzi. Bahá'u'lláh. p. 118. al-Qaṣídah al-Warqá'iyyah was first published in vol. IV of Ishráq Khávarí's Má'idahy-i ásmání;. A more complete version is in Bahá'u'lláh, Áthár-i qalam-i a'lá. 1II. 196-215. The Zaynu'l-Muqarrabin ms. was kindly provided to the auth or by the Research Department at the Bahá’í World Center, Haifa.

The meter of this qaṣídah is an irregular catalectic ṭawíl. For Bahá'u'lláh and the instance, the first line in all versions begins with the hemistich "Ajdhabatní bawáriqu anwári ṭal'atin." which does not scan. That most of the lines are regular seems to indicate that the author was taking great liberties, rather than that he was entirely without a feel for ‘Arabic meter. Some irregularities may derive from textual corruption, an issue which only a scientific edition of the poem could settle. The rhyme scheme, as in Ibnu'l-Fariḍs work, is one wherein the final syllable of each line is tá, with kasrah, preceded by fatllaḥ. However, Bahá'u'lláh sometimes maintains this rhyme by making properly masculine adjectives or verbs feminine. He also creates some fanns of verbs which have no lexicographical reality. In some cases, Persian grammatical features are transferred into the ‘Arabic. For instance, where a definite noun followed by a defi nite adjective would be used by an Arab. Bahá'u'lláh tends to make the noun indefinite. This has the effect of putting the noun and its modifier in a construct state (iḍáfah), and in fact the Persian iḍáfah performs both adjectival and construct functions. When ‘Arabic phrases are used by Persians in their own language, this is a common transformation .

The meter of the poem is an irregular catalectic ṭawíl. In some cases, Persian grammatical features are transferred into the ‘Arabic. But another source of the irregularities may lie in the Bábí and Sufi disregard for the elaborate labyrinth of classical ‘Arabic grammar, which they dismissed as a dry impediment to the spontaneous expression of mystical meaning. In his The Four Valleys (Chahár vádí), written only a few years later to ‘Abdu'r-Raḥmán al-Kirkúki, the head of the Qádiriyyah order in Sulaymaniyyah, Bahá'u'lláh related the story of a mystic who set out on a journey with a grammarian. When they came to the sea of grandeur, the mystic immediately plunged into the water whereas the grammarian grew confused and hesitated. When urged on by the mystic, the grammarian confessed that he could not bring himself to advance. "Then the knower cried, 'Forget what thou didst read in the books of Síbavayh and Qawlavayh, of Ibn Ḥájib and Ibn Málik, and cross the water! This sort of belief, combined with the Báb, mistrust of the high ulama and their intellectual tools, seems to have led Bahá'u'lláh to go well beyond the normal limits of poetic license.

Katalektisk: En katalektisk rad är en metriskt ofullständig versrad som saknar en stavelse i slutet eller slutar med en ofullständig versfot.

Bahá'u'lláh, Cháhar vádí, Áthár, III, p. 143-44; trans. Khan and Gail, The Seven Valleys and tile Four Valleys, p. 48. I have bene-fitted from John Walbridge's study of The Four Valleys.

For the Báb's strictures against philosophy, logic and the principles of jurisprudence, see Seyyed ‘Alí Muḥammad dit le Báb, Le Beyan Persan, tran s. A. L. M. Nicolas (Paris: Librairie Paul Geuthner, 1911, 2 vols .) I. p. 131 (IV :lO). These prohibitions were later abrogated by Bahá'u'lláh.

Al-Qasídah al-Warqá'iyyah is only the third or fourth earliest extant work by Bahá'u'lláh of any length or doctrinal importance, and it will prove relevant to discuss the first two pieces he wrote as a background to this poem. The first was a lso a poem, Rashḥ-i ‘Amá, which he composed in the Siyáh-Chál dungeon in Tehran where he was imprisoned in the fall of 1852. There, he underwent a series of very powerful mystical experiences .

For the "Rashḥ-i 'amá," see Ishráq Khávarí's Má'idahy-i ásmání;, IV, pp. 184- 86.

He wrote, much later:

During the days I lay in the prison of Tihrim. though the galling weight of the chains and the stench-filled air allowed Me but little sleep, still in those infrequent moments of slumber I felt as if something flowed from the crown of My head over My breast, even as a mighty torrent that precipitateth itself upon the earth from the summit of a lofty mountain. Every limb of My body would, as a result, be set afire. At such moments My tongue recited what no man could bear to hear.

Bahá'u'lláh, Lawḥ-i mubarák khitáb. bih Shaykh-Muḥammad Taqíy-i Mujtahid-i Iṣfáhání ma'rúf bih Najafi (Tehran : Bahá’í PubIishing Trust, 131 B.E. 1974-75) p. 17; trans, by Shoghi Effendi Rabbani as, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf (Wilmette, II I.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1962) p. 22.

In the poem Rashḥ-i ‘Amá, Bahá'u'lláh describes how his rapture (jadhbah) has caused the unknowable essence of God ('amá) to shower down its moisture. This is a complex play on words, utilising Sufi technical terminology. The term 'amá means in ‘Arabic literally cloud, and its theological significance derives from an oral report attributed to the Prophet Muḥammad. Abú Razín al-‘Uqaylí is said to have asked the Prophet: "Where was our Lord before He created the heavens and earth?"Muḥammad replied : "In a cloud, above which was air and below which was air." By the time of ‘Abdu'l-Karím al-Jílí (1365-1428 A.D.), the term had important philosophical and mystical associations for the school of Ibn ‘Arabi. In his Al-Insán al-Kámil (The Perfect Man) al-Jílí describes 'amá as the highest level of the divine essence which is beyond both absolute reality (al-ḥaqq) and createdness (al-khalq). Al-Jílís systern was a monist one in which the being of God was the only existence. This being or essence had created modes and absolutely real modes which correspond to the universe and God as conceived in dualistic systems. The highest of the real modes (al-ḥaqqí) was unicity (aḥadiyyah), wherein all divine names and attributes disappeared and were unmanifest. Nevertheless, the stage of unicity remains a penultimate one in which God still manifests himself (tajallí, zuhúr) as exaltation (ta'allí). The Cloud, or 'amá, however, is absolute essence – neither reality nor createdness, neither exaltation nor denigration – wherein God is altogether hidden.

See the entry for 'amá in Abu'l-Faḍl ibn Mánẓur, Lisán al-Arab, XV (Beirut: Dar Beirut, 1956) p. 99. For this hadíth. – see A. J. Wensinck, et. al., Concordance et indices de la tradition musulmane (Leiden: E. J. Brill, vol. IV, 1962), entry for 'ama, where it is noted that the tradition is reported by Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal. Martin Lings seem s to be in error when he says this word means "blindness" or "secrecy": see his A Moslem Saint of the Twentieth Century (London : George Allen and Unwin, Ltd ., 1961 ) p. 153, note 1.

‘Abdu'l-Karim al-Jílí, al-lnsán al-Kámil (Cairo: n.p., n .d ., 2 vols .) 1:35. See also H. Ritter, ‘Abdu'l-Karim Kuṭbu'd-Dín. Ibrahim al-Djílí, The Encyclopedia of Islam. rev. ed. (London : Luzac and Co., 1971 ).

Thus, although Bahá'u'lláh rejected the existential monism of Sufis like al-Jílí, he did employ the term 'ama to indicate the uttermost unknowable depths of God's essence. Since the word also means cloud, he referred to the sprinkling (rashḥ) of the Cloud of the divine essence which his own state of mystical ecstasy precipitated while he languished in the shah's Black Pit (line 1). This same rapture attracted the divine beloved's glance of bestowal and brought him into God's presence (line 4). This serves as a signal for the blowing of the trumpet that indicates the advent of the Resurrection Day (line 6), or the Day of God (line 9), brought by the promised one or "new beauty" in Ṭá (the Bábí designation for Tehran).

It seems clear that in this poem, as he lay in chains in the Black Pit, Bahá'u'lláh alluded to his premonition that he had a special role to play in reinvigorating the Báb! movement. This allusion was, however I more in the nature of a vague intimation than a forthright claim. That Bahá'u'lláh had an intimation in 1852 of his future leadership role is confirmed in his later writings. He wrote that it was in the fall of 1852, that he determined to reform the Bábí religion and instill a new vitality into this demoralised community.

Bahá'u'lláh, Abdu'l-i mubarák khitáb bih Shaykh-Muḥammad Taqí, p. 16; Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, p. 21.

In this poem also, Bahá'u'lláh mentions for the first time his houri (ḥurí), one of the angelic female figures said by the Qur'an to inhabit paradise. He saw this figure in visions, and he later identified her as the conveyor to him of the divine revelation. He apparently addressed Al-Qaṣidah al-Warqá'iyyah to her as well. Muslim mystics often addressed the divine as a female beloved, following the conventions of love poetry, but this seems to be a rare instance where the principle of revelation itself is depicted as feminine. For Muḥammad the angel of revelation had been the male figure, Gabriel. Bahá'u'lláh's houri here recalls Dante's Beatrice.

See Bahá'u'lláh's "Lawḥ al-húriyyah" in Áthár-i qalam-i a'lá, volume IV (Tehran : Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 125 B.E./1968-69) pp. 379-91.

In his second major extant work, Lawḥ Kull at-Ṭa'am (The tablet of all food), Bahá'u'lláh explored a series of metaphysical realms. This piece is a commentary on the quranic verse, "All food was lawful to the children of Israel save that which Israel forbade himself before the Torah was revealed" (3,93). Mírzà Kamálu'd-Dín Naráqí, a Bábí who had met the Báb in Kashan, requested this commentary from Bahá'u'lláh sometime in 1853, when he was in Baghdad. Naraqí had previously sought a commentary on the verse from Mírzà Yaḥyá, Ṣubḥ-i-Azal, but was so disappointed in the reply that he turned to Bahá'u'lláh for a more satisfactory answer .

This episode may have been part of a pattern wherein the rank and file were increasingly demonstrating discontent with Mírzà Yaḥyá's leadership. Bahá'u'lláh's mystical intensity and charismatic personality made him the obvious alternative, much to the chagrin of his younger half brother, whose own extreme secretiveness, caution and conspiratorial methods were to blame for the disaffection of a number of his followers. After Bahá'u'lláh's intimation while in prison of his messianic call, he may have been tempted to assert his own claims to leadership. However, he seems to have been fearful of provoking a major schism. In the event, he postponed a public proclamation of his claims to be the spiritual "return" of the Báb until 1864 in Edirne, though he made his claims known to a small group of close disciples in April 1863 in Baghdad.

Algar (Mírzá Malkum Khán, pp. 58-59) depended on a late travel diary for his faulty chronology of Bahá'u'lláh's departure from Baghdad. All Bábí sources agree that Bahá'u'lláh was ordered banished from Baghdad by the Ottoman government in spring 1279/1863, and that he left the city in Dhú'l-Qa'dah 1279/May 1863. See, for instance the "Historical Epitome" by Mírzá Javad Qazviní in E. G. Browne, camp., Materials for the Study of the Bábí Religion (Cambridge: University Press, 1918) p. 15. Qazvíní was in Baghdad at the time of the banishment. The strongest evidence for Bahá'u'lláh's date of departure is the foreign consular reports, which confirm the Bábí dates. See Moojan Momen, ed ., The Bàbi and Bahá’í Religons: Some Contemporary Western Accounts, 1844-1944 (Oxford: George Ronald, 1981 ) p. 183. Moreover, Algar's assertion that the authorities may have expelled Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Malkum Khán at the same time because there was some link between the two suffers from weak logic and a total lack of evidence. Simultaneity does not prove causal connection. Algar seems to have attempted here to buttress an old canard in Muslim writing about the Bahá’í Faith – that it had links with Free-masonry. This is wholly untrue. In fact, Bahá'u'lláh was banished from Baghdad to Istanbul in 1863 because the Iranian government, at the instigation of Shí’í ulama, put pressure on the Ottoman government to remove Bahá'u'lláh further from Iran. In Baghdad, Bahá'u'lláh still had access to Iranian pilgrims and to the Shí’í shrine cities. Shí’í clerics like ‘Abdu'l-Ḥusayn Ṭihrání were alarmed at his growing influence. As for Bahá'u'lláh's open declaration of his mission in Edirne, see his "Surat ad-Damm," Áthár-i qalam-i a'lá, IV, pp. 1-15 .

In the Tablet of All Food, Bahá'u'lláh writes a figurative exegesis explaining the mystical significance of the word food in the above-mentioned Qur'an verse. He says that it first of all refers to the throne of háhút. This term indicates a station (maqám) of divine oneness inaccessible to human understanding. He says that the esoteric and exoteric aspects of this station are identical. Háhút is formed according to the same Syriac pattern as more familiar words such as násút (humanity), and it probably derives from the letter Há, which stands for huwiyyah, or God's self-identity. In the next station, láhút (divinity), the phrase "He is He, there is none other than He" applies. This refers to God's unity and uniqueness, and only the most purified and holy of worshippers can understand this station. In the next lowest station, jabarút (the realm of divine dominion), the phrase 'Thou art He and He is thou" obtains. On this plane prophets may use theopathic language, identifying themselves with God on the level of His attributes. Then comes the station of malakút (the realm of divine power), which is inhabited by those of God's servants who have detached themselves from the riches of the material world. At the lowest level subsists the station of násút (humanity). Bahá'u'lláh describes the universe as a hierarchy of stations. The lowest is that of pure humanity, but human beings can attain or comprehend higher stations by acquiring certain attributes. God reserves the higher stations to saints and prophets, while the highest, háhút, remains impenetrable to all but God. This sort of schema often characterised Sufi works.

Lawḥ kull aṭ-ṭa’-am in Ishráq Khávarí's Má'idahy-i ásmání, IV, pp. 269-70.

Esoterisk: Förehållet en mindre krets invigda. Förborgad.

Exoterisk: Även tillgänglig för personer även utanför en viss krets av invigda. Tillgänglig.

Teopatiskt: känslor som uppstår när man betraktar eller mediterar över Gud.

For the terms jabarút and malakút, see ‘Alí al–Jurjání, at Ta'rífát (Cairo, al-Khayriyyah Press, 1306/1888) p. 119.

Bahá'u'lláh's stations thus differed from al-Jilí's graduations in the divine essence, since Bahá'u'lláh rejected existential monism. He looked upon the stations below háhút as levels of God's creation, but not as manifestations of the divine essence itself. In fact, the Shaykhí-Bábí tradition opposed Sufi theories of the unity of being from the time of the founder of the movement himself. Shaykh Aḥmad al-Ahsá’í composed a spirited attack on this idea as developed by the school of Jilí entitled ‘Ayn al-Yaqín (The eye of certainty). Bahá'u'lláh himself often wrote that even the devoutest mystics and the prophets were unable to behold God or apprehend His essence.

Aḥmad al-Ahsá’í, ‘Ayn al-yaqín, UCLA Special Collections, Shaykhi Collection, 1053/C, Box 1, ms. 3. The Báb condemned the doctrine of waḥdat al-wujúd as polytheism (shirk) in his Ṣaḥífahy-i 'adliyyah, see MacEoin, "The Concept of jihad," note 103.

See the "Lawḥ-i Salman" in Bahá'u'lláh, Majmú'ahy-i maṭbu'ahy-i alváḥ-i mubárakah (Cairo: Sa’adah Press, 1920) pp. 128- 60.

In turning to Bahá'u'lláh's al-Qasídah al-Warqá'iyyah, we find that his theological and metaphysical ideas, his millenialism, and his vision of the celestial maiden, the houri, have all deeply affected the content and even the structure of the poem. Like Ibnu'l-Fariḍ's Naẓmu's-Súlúk, Bahá'u'lláh's ode consists of both a dialogue and a soliloquy. But in the former, lbnu'l-Fariḍ plays down the elements of dialogue, especially once the mystic claims to have attained union with his beloved. In Bahá'u'lláh's work, the dialogue continues throughout, and this partially reflects a theological position. Since Bahá'u'lláh's theology ruled out the sort of essential union between the mystic and God in which Sufis such as Ibnu'l-Fariḍ and Ibn ‘Arabi believed, his poem retains a more dialogical structure.

Ibnu'l-Fariḍs Poem of the Way falls into three sections. In the first, the poet delivers an encomium on his divine beloved, with much boasting of how he has suffered for her, and com-plaints against his calumniators who have slandered him to her. In the second, she replies briefly to the effect that he has mistaken his own self-love for passion for her, and that he must sacrifice his very life to follow her path. In the very long third section, which comprises the bulk of the poem, he states his willingness to die fo r her and even his unworthiness to obtain union with her at such a paltry price. He depicts himself as so entirely one with his beloved that when she speaks it is he who talks. He says he prays, only to find that it is to himself that he has been praying. While Ibnu'l-Fariḍ makes it clear that he does not constantly enjoy a state of blissful union, Bahá'u'lláh's poem never really attains this peak at all. God remains utterly transcendent; the most that can be accomplished is to arrive in the presence of God (liqá'u'lIah), which is the presence of His attributes rather than His wholly unknowable essence.